[Note: I have moved to publishing blog posts here, instead of this Aftenposten-specific context]

I used to think that strategy, and product strategy specifically, was a complex document that laid out a plan for how all aspects of the product would be shaped in the coming months and years. What I’ve found is that product strategy is much more effective when it is a brief presentation that follows a simple structure, explaining what the problems are and how we think we might solve them. The simplification itself might be hard, and will require interpreting insights from a wide range of domains, but I’ve found that the simplicity of the three-step model I’ll share below makes it much easier to both communicate and discuss the choices made in the strategy.

What some companies call a product strategy is often just a description of the business model and the goals (not the strategy) for those business areas. For media companies, we can easily fall into the trap of thinking we have a strategy once we’ve established a goal of something like “generating subscription and advertising revenue by engaging more users with a delightful product experience and journalism that matters”. Some companies will also add that the employees should be happy, as if there is an alternative to that goal. These are all good things to establish as overarching goals, but they will not give you clarity on product strategy simply because they don’t say anything about how you’ll get there.

A slightly better version of product strategy, albeit not adequate, is a description of what the product experience would be like if the team had unlimited time and resources. It describes the type of product the team tries to create in the long run, but not the tough choices it will need to make in the coming 12-24 months. It is therefore more of a product vision than a strategy: It provides useful context for the strategy by describing the future we are trying to create in the next 2-5 years, but it does not help us decide which bets to prioritize in the near term. It also rarely generates good discussions, because it is much easier to agree on a future vision than near-term priorities.

As Richard Rumelt explains in Good Strategy, Bad Strategy (2011),

[A good strategy] identifies the one or two critical issues in the situation – the pivot points that can multiply the effectiveness of effort – and then focuses and concentrates action and resources on them.

Our expectations for product strategy should be similar. It should be specific about our most important problems and our hypotheses for how we might solve them. In Rumelt’s words,

The purpose of strategy is to offer a potentially achievable way of overcoming a key challenge.

He says “potentially” because we should not expect certainty about the solutions, but instead plan to test several approaches to solving the problems identified. More about this later.

In my own approach to product strategy I have taken inspiration from both Rumelt and former Netflix CPO, Gibson Biddle, who has created an excellent explainer of his thinking here. In my experience, also when it comes to product strategy, it makes sense to stick to Rumelt’s strategy kernel, here adapted to a product context:

Diagnosis: Identification of the biggest challenges to solve

Guiding policy: A set of overall strategies you believe might solve the challenges

Coherent actions: The tactics you’ll employ to deliver on each strategy, expressed in your OKRs and roadmaps

In the next few paragraphs I’ll explain how we have used this methodology in one of Schibsted’s subscription newspapers, Aftenposten.

1. Diagnosis

The real art of the diagnosis is simplification. Above all, your diagnosis should simplify the complex reality in which your product exists by identifying a few, 3-5, issues that are critical to solve now. While your company’s overall strategy and goals should play a role here, there may be more specific pieces of qualitative and quantitative insight, that only the product team will have access to, which will be even more useful:

Engagement and retention: Which user groups do we retain and which ones churn? How do their behaviours differ? What qualitative insights do we have about those who churn and those who stay?

Non-users and market potential: Which users are we not reaching today? What are their needs? Are there profitable segments that we can reach by serving a different product experience (and business model?).

Barriers to success: What internal and external barriers are preventing us from delivering a better product? Why do those barriers exist? Can they be removed?

Matt O’Brien uses Elon Musk’s Space X as a great example of a clear diagnosis:

What’s preventing humans from colonizing other planets? The critical bottleneck is cost. It’s simply too expensive to get to the nearest habitable planet (Mars). The main source of expense is that we don’t reuse rockets — we let them burn up in the atmosphere after delivering their payload into space. It’s as expensive as air travel would be if we burned the 747 and made a new one each time. “SpaceX believes a fully and rapidly reusable rocket is the pivotal breakthrough needed to substantially reduce the cost of space access.”

In Aftenposten (Schibsted’s largest subscription newspaper), the diagnosis in the product strategy is summed up in four points:

2. Guiding policy

The guiding policy may in some cases be about just one thing, but typically it involves a set of strategies meant to address the wide range of challenges described in your diagnosis. It doesn’t require full certainty. On the contrary, you should expect that some of your strategies will be proven ineffective. At this stage, you may use hypotheses for solutions from anyone in your organization, but make sure you have a consistent way of evaluating and prioritizing these ideas. I find it useful to use Gibson Biddle’s DHM framework:

D: How will this idea improve our ability to delight our customers?

H: What aspects of this idea are hard-to-copy?

M: How will this idea improve profit margins?

With these criteria in mind, it is easier to prioritize those that will build a lasting advantage for your product, making you better than the competition at solving the most important user problems. People rarely remember more than five, so I’d say max five per product team.

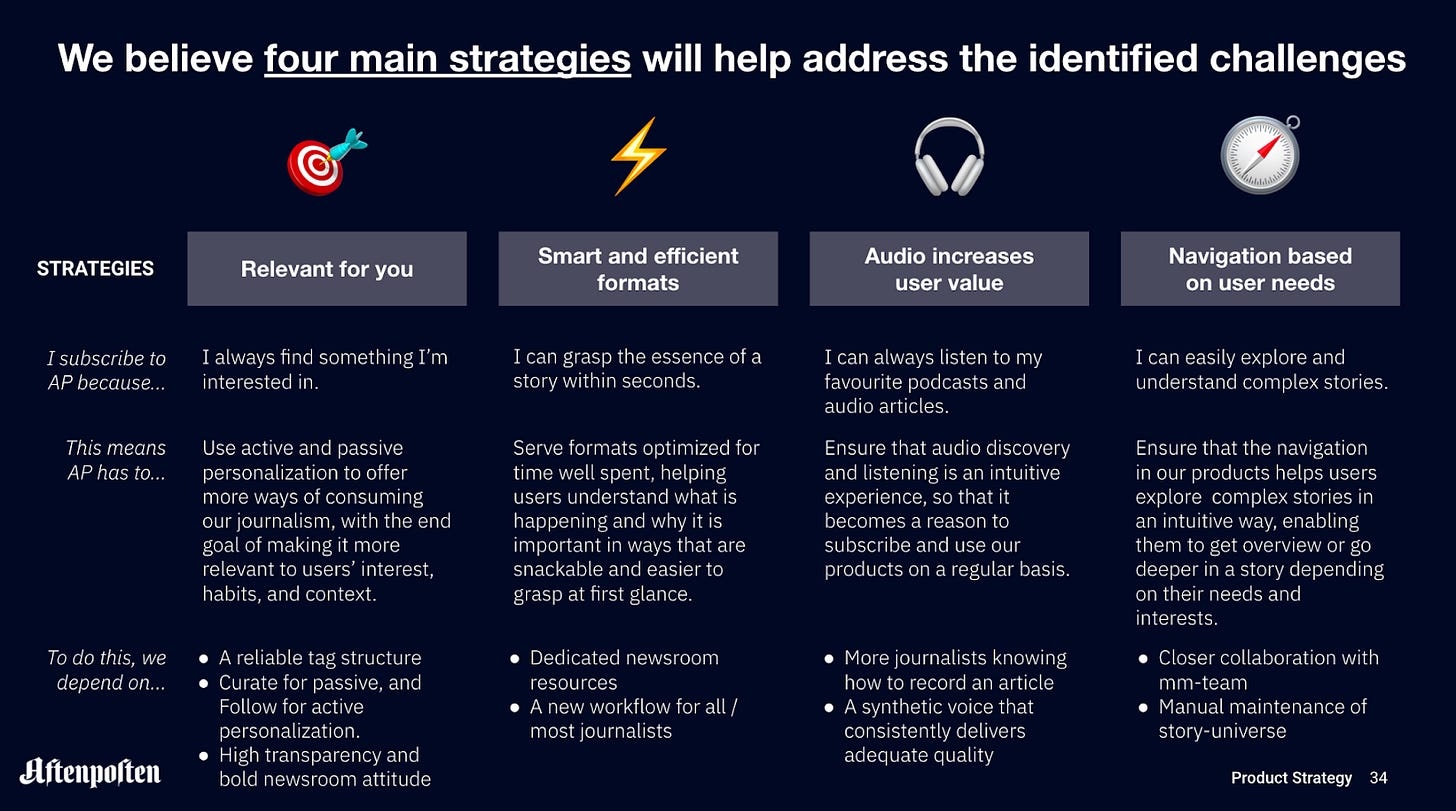

In Aftenposten’s case, the strategies prioritized for 2022 in the core product team were summarized in four columns that each communicate:

How this strategy will help us delight our users and convince them to subscribe

What kind of product experience the Aftenposten team would need to build

Dependencies the organization needs to be aware of, so that they don’t become blockers for execution

At this point, we can’t know for sure whether these are, in fact, the best strategies for solving the identified problems and, ultimately, reaching the company’s overarching goals. And that fact has two big consequence for our product strategy:

We have to measure if the strategy works, and need reliable metrics in place that help us measure the effect of each strategy. I prefer doing that per specific initiative / tactic, as each experiment may have very different measures of success, but the idea is the same: You need to know as early as possible whether you’ve chosen the right strategy to solve the identified problem.

We must be open to changing the strategy if it doesn’t work. This will help free up resources to double down on the strategies that do work. We all know that giving up on a strategy will be harder to do the more we’ve invested in terms of time, resources, and internal lobbying to get buy-in from the organization (and thus many companies and teams will fail to change their strategy when they really should). So it’s the same with strategy as with anything new your product team considers building: test your riskiest assumptions early.

3. Coherent actions

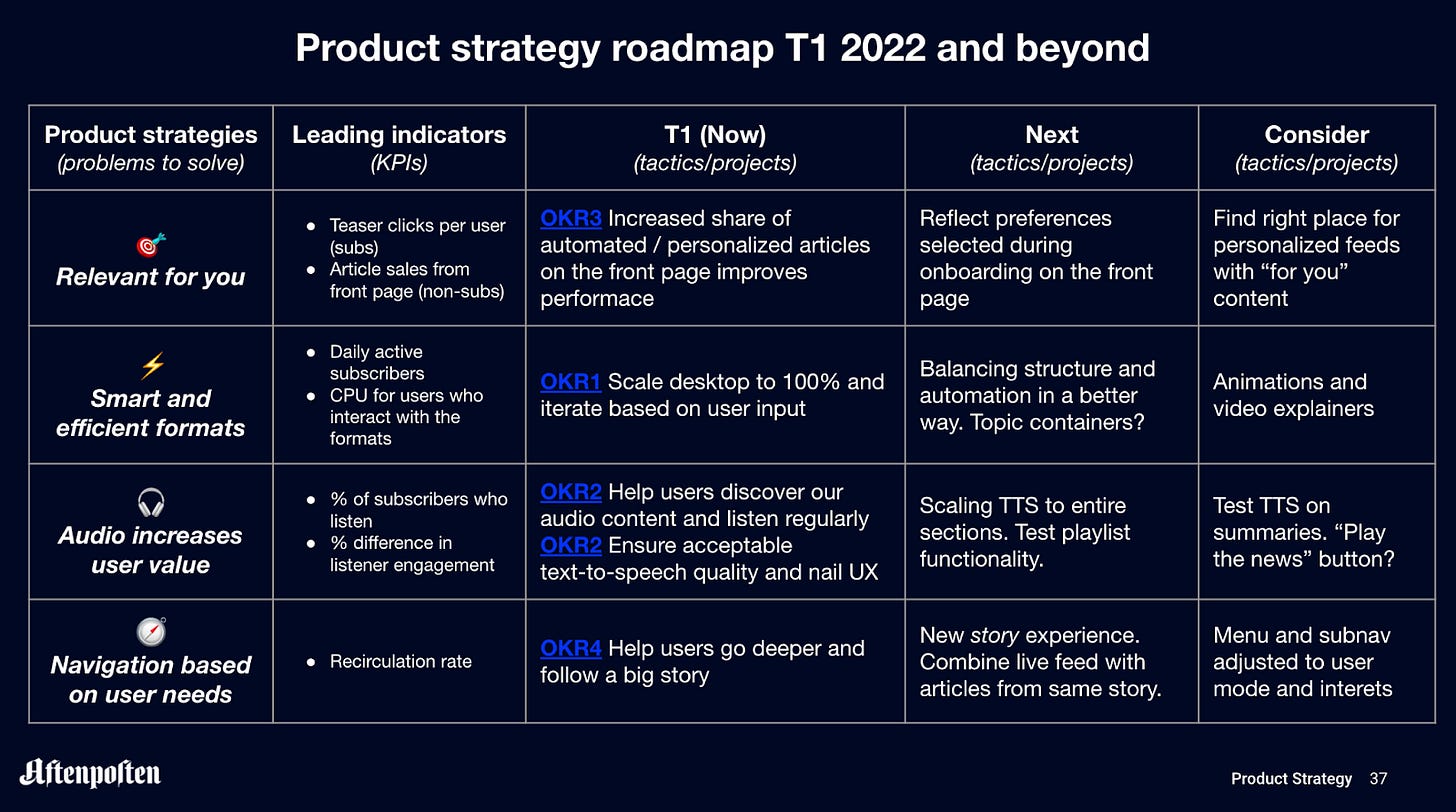

This step describes what your team will actually do in order to deliver on each strategy, and in which order it will happen. In each strategy we have a set of tactics, which in this case refer to initiatives / product improvements that can typically be tested in a few weeks, and no longer than 3-4 months. To create an overview of these actions that is accessible and understandable to both your own team and its stakeholders, I prefer using a combination of OKRs and a simple product roadmap:

OKRs: The product strategy is set for 1-2 years, while the OKRs are per 3- or 4-month period, and therefore we may at any given time have several OKRs that contribute to one particular strategy. Depending on how certain you are about the thing your team should build, the Objective may be either outcome- or output-oriented (as they both serve a purpose, in my opinion). The Key Results will be your main way of measuring the success of the strategy your OKRs contribute to.

Product roadmap: This helps communicate the order in which you’ll work on each tactic in your strategy. I like bringing it all together in a table that includes:

One row for each strategy

One column for the OKRs / tactics you’re working on now, one for tactics you’ll likely work on next, and one for tactics you’re considering (inspired by Bruce McCarthy’s Product Roadmaps Relaunched)

One column listing the KPIs that you use to measure the success of your current tactics / OKRs.

For Aftenposten’s product team, it looks like this:

Keep it short

That’s it. The core of a product strategy consists of the problems you’ve chosen to focus on, your overall approach to solving those problems, and a plan for the order in which your team is likely to work on each tactic. You should be able to visualize those things in 3-4 slides. My experience is that keeping it short then becomes a forcing mechanism for clarity on what problems you see and how you think they might be solved.

—

Let me know if you have questions or thoughts - or even more interesting, if you disagree with key elements of this article!